Thirty Years on South America’s Great Frontier

By John O. Browder

January 2012

[Click here for Table of Contents]

Introduction

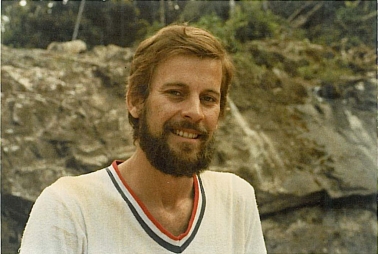

Thirty years ago I landed in Brazil, a scruffy young North American graduate student beginning field research for a doctoral dissertation on Amazon regional development. The endeavor would set the course for most of my professional life. Now, as I begin my second term as the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs in the College of Architecture and Urban Studies at Virginia Tech, I wish to share my story of these colorful thirty years, in an informal voice, to anyone who might be interested. What follows is not another academic paper (too many of those have I already authored), but a more personal autobiographic journey that summarizes the findings, and stories behind them, of the 20-some Amazon research projects I pursued since 1983. I conclude with some general reflections on the regional development experience of the Brazilian Amazon since 1964 that may be of interest to scholars of globalization and international development, and all of my other my Amazonista friends.

My father taught property law and trusts and estates at the University of Michigan for 40 years (1953-1992). He died in 2007 and I have been reading his published work ever since. In one of his many papers published in the Michigan Law Review, entitled “Giving or Leaving-What is a Will?,” Dr. Olin L. Browder, Jr. raises a simple, yet amazingly complex question: Is there a difference between giving away something of value while we are alive, or leaving “it behind at our death, directing who will receive it at that time?” This question has intrigued me as I reflect on the last 30 years of my life working in the Amazon. The word “will” has two meanings – the (1) “will” to act now in relationship with other co-existing beings, and (2) the last “will and testament” of someone who is about to die in order to be remembered in certain ways by selected descendants. But, the two disparate meanings of this word also converge at an ethical focal point: Do both manifestations of “will” bring us to a clear duty? Montaigne stated it this way:

“We cannot be held to what is beyond our strength and means; for at times the accomplishment and execution may not be in our power, and indeed there is nothing really in our own power except the will: on this are necessarily based and founded all the principles that regulate the duty of man.”

My father also wrote about the “Taming of Duties,” but we won’t go there today.

The people you will meet in this story certainly had a will to survive, by the only means available to them – tearing down tropical forests and planting crops. But, almost all of them also sensed a duty to leave to their children the means for them to experience better lives on this same landscape. This is what we all wish for our children, no matter what country or culture we live in. This is also the will, the conscience of the Amazon, today.

The landscape will remember our presence. It is what we leave behind, our “last will and testament,” our unwitting autobiography – the Will of the Amazon.

My story begins in 1983 and is organized around 6 externally-funded research initiatives that I was privileged to lead during the following thirty years. I resist the temptation to “adventurize” these 30 years, but it would be easy to do so. It would be easy to sprinkle this story with many interesting, even tense, dramatic moments, like the day I drove into the national protected Guapore Biological Reserve with a small film crew in 1984. As we entered the Reserve, a mile-long convoy of bull-dozers, skidders, front-end loaders, trucks laden with mahogany logs escorted by an armed informal militia, all told perhaps 100 men, hastily retreated in the opposite direction. Witnessing this extravagant violation of federal forestry law, it is amazing that we lived to tell the story.

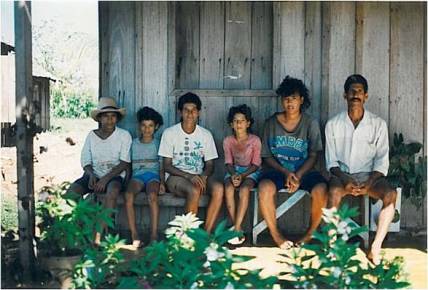

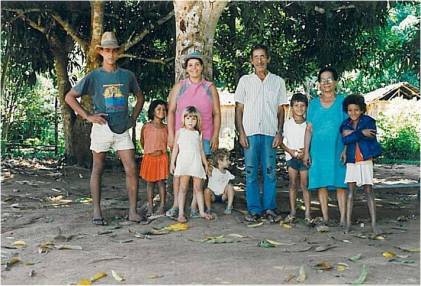

It is also filled with warm memories of the 57 young Brazilian students who signed-on to work as interviewers on those 20 survey research expeditions, for many of them their first experience in the Amazon. These students were referred to us by amazing faculty from 10 Brazilian universities, with which I became affiliated over these 30 years [click here for Photos (1) (2) ]. Most of all, as I reflect on my time in Brazil, I cherish the memories of the friendly, hospitable people who settled in Rondônia, who opened their homes and lives to me and my research teams, the people of Rondônia, and their amazing life stories, generously shared with me so that I might better know their world [click here for Photo Gallery].

So, for those of you interested in this story, please read-on. I summarize those 30 years in the following pages, offering a synoptic review of my Amazon research endeavors and summary findings to date, some of which are new. There are several “side-bars” – hot-links to stories, slide shows, and posters that deepen the narrative. Welcome to the “Will of the Amazon.”

Chapter 1 (1983-86)

Logging the Rainforest: A Political Economy of Timber Extraction and Unequal Exchange in the Brazilian Amazon:

In 1988, disturbing satellite images began to appear across the global press media (Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, Nova) revealing the conflagration of the Amazon Basin’s rainforests on an unprecedented scale. When I arrived in the Brazilian Amazon five years earlier to undertake my doctoral dissertation research on the regional economic impacts of the Amazon’s burgeoning timber industry, the tropical deforestation spectacle had not even begun to make the news in the Global North.

My dissertation research focused on how within the short span of 5 years government export promotion policies had subsidized the horizontal consolidation, and then vertical integration, of Brazil’s wood processing industry into an oligopoly of a half-dozen powerful Brazilian multinational trading companies. These trading companies effectively seized control of tens of thousands of hectares of Amazonian forest-land, subordinated a burgeoning sector of small-scale independent lumber producers into exploitative exclusive production contracts, and launched armed expeditionary logging militias hundreds of kilometers into federal forest lands, including indigenous and biological reserves, to conquer the Amazonian timbershed in search of one commercially prized hardwood species – Brazilian mahogany (Sweitenia macrophyla, King). A ravenous feeding frenzy of totally unregulated logging ensured – the Brazilian “Mahogany Boom” – from 1980 to 1985. And then it crashed.

Apart from nearly bankrupting the region’s industrial wood sector – precisely the opposite outcome envisaged by Brazil’s export promotion program (Browder 1987 and Browder 1989), and driving the mahogany species to near extinction – (after much wrangling mahogany was listed on the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species in 2003 [http://www.cites.org/eng/prog/mwg.php]) – the Mahogany Boom opened access to thousands of square kilometers of Amazonian forestland to follow-on settlement by small farmers, land speculators, and cattle ranchers in frontier areas of Pará, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia.

Encouraged by government colonization programs, tens of thousands of former coffee plantation sharecroppers, turned into landless peasants by Brazil’s shift to large scale mechanized soybean production in the Southeast and South (1966-78), eagerly packed-up and migrated to frontiers like Rondônia where government promises of free land on 100 hectare parcels offered hope for a new life – the chance for the landless rural laborer to own land. These family farmers, who produced Brazil’s food basket in the sub-tropical climate South and Southeast between coffee harvests, took their traditional cropping practices with them to the tropical North (Amazon).

These are among the people whose lives I would accompany for the following 25 plus years in a series of research and development projects on smallholder settlement and agrarian change, neo-tropical agroforestry, frontier urbanization, the cattle industry, and regional development of the Brazilian Amazon.

The centrifuge of the Brazilian Mahogany Boom was Rolim de Moura, Rondônia, an obscure, bustling boom-town that hadn’t even made it to the official road map of Rondônia by 1980 (probably because there was no reliable road to get there). Even so, every major Brazilian commercial bank had a branch office there by 1985 (eight, in total). Indicated to me by several of the largest two dozen mahogany exporters I interviewed in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo in 1983-84 as the primary source of Brazilian rough-cut board mahogany lumber, “Rolim” would be the first destination on my dissertation field research journey.

Mahogany logs stocked for milling, Rolim de Moura (1984)

The Industrial Sector after the mahogany boom, Rolim de Moura (2002)

After the Bust -- Industrial Sector, Rolim de Moura (2002)

In June 1984, after a 3 day bus- ride starting in Belém do Pará, and spanning some 3,000 kilometers, I alighted in Pimenta Bueno, Rondônia, and hopped onto the local bus (a retired Bluebird) for the last 60 km segment of my journey to Rolim de Moura. The driver, an emaciated, but jovial kid wearing a Talking Heads tee-shirt and a 3-day beard, delivered me to this brave new world, a smoky, dusty lumber boom town, burning with filth, dreams, and violence, at the “end of the world”.

Dropped at the bus-stop on the town’s congested and dusty 25 de Agosto main street, I asked a passersby for the location of the sede de municipio (town hall) and there presented myself to the chefe de gabinete, the doorman and gatekeeper to the town mayor. Inside his waiting room jammed with local constituents seeking favors, the acting mayor of Rolim de Moura, Sr. Adegildo, quite unexpectedly, received me immediately. He stated how honored he was that I was the first norteamericano ever to visit his town, just 7-years old. Before long, the mayor passed me to his large, burly bodyguard named “Bezinho” (“Little Bull”). Bezinho provided a sound barrier-breaking tour of the town’s dusty streets in the municipio’s only official vehicle, a fusca (Volkswagon beetle), eventually delivering me to Rolim’s only hotel, the de Colores, a brothel.

The tour, which included an ominous attraction, the town’s cemetery (I guessed there were a thousand tombstones – a haunting reminder of the realities of the frontier), also featured the town’s setor industrial. There, at last, I cast my eyes upon the great crucible of Brazil’s mahogany trade, 34 raucous lumber mills, churning day and night. For a town of 5,000-20,000 inhabitants (the mayor was uncertain about the exact number of his flock), these 34 lumber mills made Rolim de Moura the “mahogany capital” of the world. Sixty-five percent of the estimated 81,650 m3 of rough mahogany board lumber sawn there in 1983 (up 167% from 30,680 m3 the year before) was exported. The lumber industry in Rolim de Moura employed 40.6% of the local labor force in 1985, generated 67% of local household income, and produced US$ 16.9 million in gross revenues, giving the trading companies a return on investment of 24.2%. [click here for story].

That evening I took supper at a local dry goods store, with a pool table and a kitchen, whose cook served surprisingly good food. The following morning the owner of the de Colores hotel asked me where I had taken dinner the night before and then informed me that a man had been shot dead there sometime shortly after I had left – another unwritten story, another tragic tombstone for this frontier town’s burgeoning graveyard. Day One, and this was already becoming the Wild West experience that I could only have imagined.

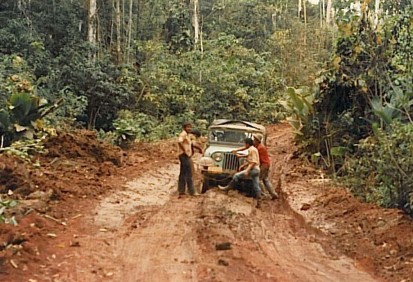

A few days later, I was invited by one of the larger lumber companies to produce a film (home video, really) about their timber extraction process, deep in the forest. The company, called Dinamo, was cutting mahogany about 100 km from Rolim de Moura, a 12 hour Jeep drive on the back country’s appalling logging roads. At the time, I had no idea that the company was illegally logging mahogany from the Guapore Biological Reserve. This 6-day side-trip, right on my dissertation topic, provided an up-front, ground-level view of the mahogany logging process, and the consequences it reaped [Click here for photo gallery]

By April 1985, the Mahogany Boom busted, leaving foreign markets flooded with cheap, Brazilian government subsidized mahogany products and Amazon sawmills inundated with thousands of unsawn mahogany logs that were left to rot in the region’s wrenching seasonal rains the following year [click here for story].

Stuck in mud

In this first chapter of my career, I began to appreciate the central role that Brazilian government policy was playing in both the opening of the Amazon frontier and its settlement and spatial organization. These policies enabled large Brazilian trading companies to prosecute a program of selective de-industrialization, the cannibalization of existing family-owned and capitalized lumber enterprises, that might otherwise have provided the backbone of regional development in the Amazon. Clearly, these big trading companies had no time or interest in the future, in “Wills” or covenants concerning the Amazon. But their willfulness, in the pursuit of personal profit, left a legacy that would be imprinted on the cultural identity of Rondônia for the duration of the pioneer generation on the Amazon frontier.

Chapter 2 (1987-88)

Public Policy and Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon (1988):

The mahogany boom that captivated my imagination during my dissertation years also alerted me to something more pervasive that would frame the deforestation discourse and my career trajectory for the next 25 years: The determinative role of Brazilian public policies, not only in structuring the frontier experience generally, but also, more specifically, in driving deforestation trends in the Amazon.

Somehow learning of the yet unpublished work of this unknown doctoral student from the University of Pennsylvania, in 1985 the Washington D.C.-based think tank, the World Resources Institute (WRI), invited me to prepare an analysis of the economic and environmental impacts of Brazilian public policies on tropical forest conversion in the Amazon. The resulting report, which focused on 3 major public Amazon regional development policies, also presented preliminary economic and financial analyses of government subsidized cattle ranching in the Amazon. This research was subsequently published in a book by Cambridge University Press (Browder 1988a Part I and Part II). The report unequivocally proved that Brazil’s government programs to develop the livestock sector in the Amazon by subsidizing large private corporations, many based in São Paulo, were directly responsible for approximately 65% of the observed deforestation in the region. Moreover, my research demonstrated that those projects were financially unviable, unproductive investments, bleeding Brazil’s Treasury to provide otherwise profitable corporations with lucrative long-term tax-break windfalls. Most of the corporations surveyed in this research admitted that the “incentivos fiscais,” the ability to capture the “institutional rents” the policies provided, was their primary reason for investing in these otherwise money-losing Amazon ventures that required the beneficiaries to deforest (convert forest to “productive” land, i.e. pasture). [Click here if interested in the “hamburger connection” or the “Social Costs of a Quarter-pounder”].

Doctoral Students Take Note (click here)

The cattle sector would continue to be a central subject of my research activity in the Brazilian Amazon, as it evolved from the a sub-national subsidy sink-hole in the seventies, to a gargantuan behemoth – the world’s largest producer and exporter of commercial beef products by 2005 – a global economic powerhouse. How would all of this affect the Amazon’s rainforests and its ever growing population – read on.

Chapter 3 (1990-1997)

Rain Forest Cities – The Urban Transformation of the Brazilian Amazon

Then, in 1989, in Phoenix, Arizona, I got side-tracked by this urban geographer from Vassar College, who had been working in a different part of the Brazilian Amazon (central Pará) and had noticed something different going on, something I was also seeing in Rondônia.

Despite its floral exuberance and tropical mystique, and traditionally rural and forest populations, demographically, according to my Brazilian mentor and dear friend, the pre-eminent Brazilian human geographer, Dr. Bertha Becker, “the Amazon was born urbanized.” What Dr. Becker was referring to was not the Amazon’s urbanization rate (or percentage of a population residing in urban areas) – now approaching 70%, but the urban orientation of the socio-economic interests that opened the Amazon region in the first place. Since 1970 the Brazilian Amazon has become a living laboratory for observing the urban transformation of a frontier, perhaps the last great frontier the world will ever see. How have urban interests influenced the patterns and processes of agrarian and environmental change in Amazonian frontier? What nascent settlement network patterns have emerged on this spatial tabula branca since the opening of the Amazon frontier? How well do leading theories explain these phenomena? [Click here for photo gallery].

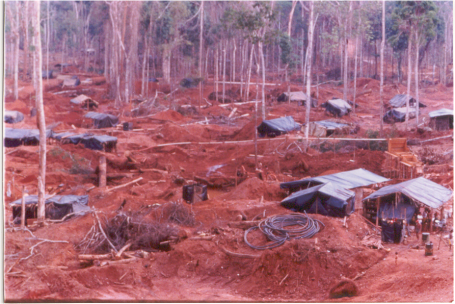

Gold-mining expeditionary settlement in southern Pará

Courtesy of Brian Godfrey

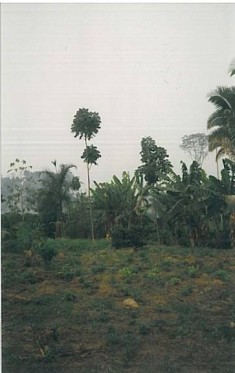

Agrovila on Transamazon Highway (ca. 1978)

Rainforst Cities: Urbanization, Development and Globalization in the Brazilian Amazon (1997), published by Columbia University Press, was the product of an 8-year collaboration with my friend and colleague, geographer Brian J. Godfrey from Vassar College. Hatched in the unlikely desert city of Phoenix, Arizona , Brian and I first met at the Association of American Geographers meeting there in 1989 and opened a discussion about our informal observations of the rapid emergence of towns and cities and urban networks in the different areas of Amazonia where we had been working. We were both intrigued by the changes we had witnessed in a few short years. Brian worked on the Xingu corridor in Pará, and I was firmly implanted in Rondônia (BR 364). A comparative case study research proposal seemed promising and was prepared and the National Science Foundation agreed to support it.

An elaborate survey research project was organized involving nearly 30 Brazilian and North American students, trained as interviewers. In June-August 1990, over 1,200 urban households in 6 different urban centers were interviewed using a standard questionnaire developed in collaboration with demographer Dr. Donald Sawyer, then on the faculty at the Federal University of Minas Gerais. Several research subprojects were initiated concurrently (including revisits to the lumber mills I had surveyed as part of my dissertation research 6 years earlier and a new rural sector survey of farmers, building on the first survey I did in Rolim de Moura in 1985). Some of the results of our urban research were surprising:

- Settlement system evolution was not a homogeneous phenomenon. Settlement patterns in Rondônia – what we called a “populist frontier” (because land was given freely to anyone) – loosely resembled the patterns predicted in Central Place Theory (Christaller, 1933), the classic urban location paradigm in European agricultural economies. However, the emerging settlement system in Pará – what we latter called a “corporatist frontier” (because land ownership was skewed toward corporate interests and big projects in the frontier there) – was not as obedient to these same master central place principles of spatial organization. The diverging configurations of settlement system patterns we found throughout our Amazonian study areas, resulting in a panoply of polymorphous urban nodal networks, called into question any unified explanation for urban settlement system evolution. We called the phenomenon “disarticulated urbanization” (actually it would be more precise to call it “differentially articulated urbanization” – since multiple logics of spatial organization explain the highly variegated networks found in different settlement fronts of the Amazon).

- Internal migration patterns were more complex than current theories predict. Our research findings also challenged conventional theories about urbanization being driven by dominant rural-to-urban migration flows, an important discourse among demographers especially regarding developing countries. When we reconstructed through detailed household surveys the geographic pathways of our urban survey respondents we found that while for 50% of the sample a traditional rural-to-urban movement explained the last household move, upon closer examination the household move prior to that for 23% of the sample indicated an urban-to-rural-to-urban trend, meaning that a significant proportion of the migrant population of Rondônia, had urban living experience before migrating to this agrarian frontier. The emerging towns, especially in Rondônia, could not be characterized as “cities of peasants” – most of the Amazon’s population had already lived in urban centers – giving further saliency to Dr. Becker’s assertion of the Amazon being “born urbanized.” As property ownership patterns began to emerge from our survey data, it became clear that rigid analytical divides like “rural vs. urban sectors” were not going to fare well in our empirical understanding of the highly complex migration phenomena we observed in the Amazon frontier. A majority of the Amazon’s pioneer settlers were connected to both urban and rural places in various ways.

- Environmental Impacts of Frontier Urbanization. While some modernization theorists have argued that increasing urbanization tends to lead to agricultural intensification and reduces wasteful extensive farming practices, thereby enabling environmental conservation, our research found that as rural property ownership progressively shifted to absentee urban-based rural property owners, those properties grew larger than traditional owner-operated family farms, and deforestation increased, pasture and abandoned fallow areas were greater, rural populations diminished, and a sizeable fraction (20%) of rural properties, owned by urban residents, produced nothing at all. In other words, in the Brazilian Amazon context, urbanization correlated with consolidation of the agrarian “rural sector” into higher deforestation rates and a less productive agriculture.

Rapid Amazonian urbanization has also fueled a rapidly growing demand for electrical power, and the Brazilian government has moved aggressively to harness the Amazon River basin’s immense hydroelectric potential (some 100-200,000 megawatts) through an ambitious program of dam-building. Twenty years ago plans for hydroelectric development would have entailed the inundation of an estimated 100,000 square kilometers of forestland, with significant social displacement and public health consequences. The rapid expansion of the region’s two major metropolitan centers, Manaus and Belém, is found in the bulging peri-urban shantytowns of these dynamic urban hubs, each year rolling back adjacent forest and farmlands into sweltering hovels of urban squalor without utilities, sanitation, or potable water. The environmental and public health consequences have been enormous

I have a great desire to return to Brazil to study the patterns of regional metropolitan growth that have been taking place in Belém, Manaus, and now in Santarem, Porto Velho, and Ji-Paraná (Rondônia). The innumerable connections these metropolitan centers have with rural Amazonia, the national economy, and the global tides of economic, social and cultural change have become, for me, the most exciting arena of future research on the Brazilian Amazon, a promising direction for potential doctoral students.

The Urban-Rural Interface

My collaboration with Brian Godfrey on frontier urbanization in the Amazon combined with my work on the social factors spurring deforestation in the region led me to consider the relationship the two. A growing body of empirical research on the causes of tropical deforestation during the 1980s and 1990s recognized the impact of rural-based agents (ranchers, farmers, agribusiness) forest cover change in the region and a slew of household-level studies ensued. But, nobody seemed to ask, what roles do urban areas play in the deforestation causal matrix? Perhaps, it was because there were no useful analytical frameworks from which to even approach the question of the relationship between urbanization and deforestation. I attempted to address this lacunae with some ideas that were published in 2002 by the journal Urban Ecosystems, entitled “The urban-rural interface: Urbanization and tropical forest cover change.” [click here for article]. In a region where the functional boundaries between rural and urban are practically meaningless (see Rainforest Cities, chapter 8), I identified 33 different variables that represent functional linkages between urban and rural areas in the Amazon. I then proposed a multi-domain network schematic representing a farmer’s (rural land owner’s) land use decision tree in which these variables operate. The resulting paper was my feeble attempt to formulate a general framework researching the urban-rural interface. Some of you may be interested in this topic.

Chapter 4 (1992-98)

Rebuilding the Brazilian Rainforest – the Rondônia Agroforestry Pilot Project RAPP). [click here]

The most important Amazon research endeavor I undertook came to me by surprise. In January 1992, I received a phone call from the representative of a Pittsburgh-based private foundation asking me what I would do with a grant of $250,000, a fairly sizable seed grant for a social scientist at the time. This gentleman had read my edited volume, Fragile Lands of Latin America: Strategies for Sustainable Development (Westview Press, 1989) and declared that the foundation was interested in supporting alternative, sustainable forms of agricultural production and natural resource management involving people in the tropics. What would become the most exciting part of my research story started as an experimental rural development demonstration project- the Rondônia Agroforestry Pilot Project (RAPP). [Click here for short side-bar story].

In June 1992, we launched a baseline survey of 240 farms in 3 settlement areas of Rondônia from a stratified random sample. Based on this initial baseline survey, 50 farmers were invited and joined our experimental group of agroforestry pilot project farmers, the rest served as a control group. After consultations with the 50 experimental group farmers, agroforest pilot plot plans were developed, each on a small one-hectare (100 square meter) experimental planting area of already deforested land. Experimental group farmers were given a menu of 25 different native Amazonian plant species (except for one, teak, which had been successfully introduced into neighboring Mato Grosso state by a private forestry company about 20 years earlier). Farmers configured their agroforest plots around 3 different models: timber-based plots (which focused on long-term production of tropical hardwoods, accompanied by short or medium-term perennial crops); non-timber-based plots (medium-term perennial fruit and annual crops, without timber), and mixed-species plots (a combination of short/medium term perennials combined with some long-term timber production). Informed by rather limited regional reforestation research literature at the time, the knowledge basis for our project’s experimental design was, by necessity, rather speculative, which makes the RAPP’s results all the more remarkable. While all of the species in our suite had passed various demonstration trials for suitability under controlled field conditions, many had not been tested in situ, under actual uncontrolled “on-farm” conditions. Here the RAPP may have made a significant breakthrough. Most of the stereotyped “scorchers and torchers” of the rainforest were looking for alternatives to their slash-and-burn farming practices, enabling new ground-breaking possibilities – like agroforestry – to take root, and, as we quickly learned, flourish. [Click here to visit photo gallery of the Rondônia Agroforestry Pilot Project].

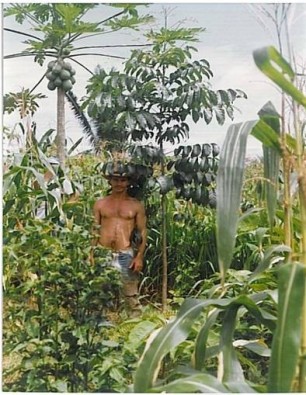

Agroforest Plot in Year 1

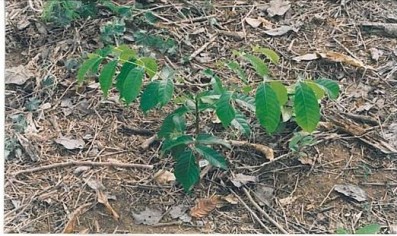

Mahogany at 12 months

We purposively designed the experiment to minimize external “interventions” (e.g. extension support, direct farmer financing, etc.), intending to closely mimic the situations in which farmers would find themselves were they to adopt this innovation entirely on their own, without external support. Apart from the assistance in preparing the agroforest plot plans (croquis), the project delivered the farmer-selected seedlings (several hundred each) to the farm gate; the farmers were then responsible for planting and maintaining their plots with their own resources. There was no farmer training (except for bee-keeping and tree seedling production), no follow-up technical extension, no marketing infrastructure established, no standardized planting site preparation protocol, no labor provided, and farmers received no cash payments for any project implementation expenditure they might incur through their participation in the project. They were left to go it alone starting in 1993, when the first batch of seedlings was delivered in black plastic bags to their farms.

Two 3-year old Mahogany trees

We revisited the project sites annually for the following 5 years, taking measurements of seedling growth, mortality, and documenting soil chemistry, diverse farmer management practices, and changes in baseline variables (household composition, employment, land use, assets, etc.). We then completed a 10 year re-survey of all 240 original properties in 2002, now subdivided into 282 farms (including the 50 RAPP experimental farms). Another follow-up survey was completed in 2003, resulting in a paper co-authored by my doctoral students, Percy Summers and Marcos Pedlowski (2004)on tropical forest management and silvicultural practices of small farmers in the Brazilian Amazon. The latest survey of the RAPP experimental group farmers were undertaken in 2010, 18 years after the project’s start, 14 years after the project’s original donor financing ended. The results of the first 12 years of the RAPP experience were reported in the journal Agroforestry Systems (2000, 2005). Collaborative research with Virginia Tech colleagues in remote sensing also produced interesting papers on tropical forest classification from Landsat TM/ETM imagery (Budreski et al. 2007).Overall the findings of this nearly 20-year old agroforestry demonstration project are summarized as follows [click here to see award winning brochure about RAPP]

1. Eliminating Barriers to Farmer Participation in Sustainable Farming Doesn’t Cost Much: At least 50% of the farmers initially surveyed in 1992 indicated a desire to participate in the RAPP, i.e. add trees and other perennial crops to their traditional farming practices, which many viewed as self-destructive over the long-term. Almost all of the experimental farmers claimed they could not have participated in the project if they were charged the costs of the seedlings ($100-250 per farm). A small grant can do much to eliminate capital barriers to widespread participation in a sustainable development project, that several participating farmers viewed as politically liberating, as well as supportive of household livelihood. [Clicks here for an interesting side-bar].

2. Why Farmers Plant Trees – It’s Not Just About Profit: “If farmers don’t make money from an innovation, then they won’t adopt it” – is the inherited wisdom of utilitarian neo-classical economic theory. Not necessarily true. After 18 years two-thirds of the farmers participating in the RAPP continued to maintain their agroforestry plots – some becoming the only island of [by then]forested vegetation on their plots otherwise carpeted with pasture grass. Even so, less than one-third (30.4%) successfully sold any agroforest products during those 18 years. If participating farmers are not realizing a significant financial gain from their agroforest plots, then what values do they find in agroforestry? When asked whether or not their efforts to plant and maintain their agroforest plots were worthwhile, 94% of the RAPP participating farmers said “yes.” Why? Immediate financial return did not figure prominently in these farmers’ valuations: 62% spoke of the environmental importance of restoring the forest vegetation cover; 25% referred to the long-term investments in the timber element of their agroforest plots, and 13% mentioned general “environmental” reasons. One farmer asserted that “planting trees is an act of political resistance” against a political-economic regime that by forcing them to deforest locks the agrarian class into a cycle of perpetual poverty. The significance of these perceptions is heightened by the fact that 37.5% of the experimental group farmers expanded the size of their agroforest plots ( in one case from 1 hectare to 9.8 hectares, to 10% of their entire property).

3. Small-scale Agroforestry Works Well With Commercial Farming. After 18 years, we found that the farmers still maintaining their agroforestry plots for no obvious financial reason, had found ways to accommodate this land use innovation into their farming systems. Experimental group farmers, still cleared forest, planted crops, and pursued their livelihoods based fundamentally on the original economic model of slash and burn – or so we thought. But, subtle changes had emerged in the experimental group that distinguished them from the rest of Rondônia’s farming population. The agroforestry system adopters (experimental group) retained significantly larger household members (6.0 persons/household), than the control group of non-adopters (3.3p/h); they sold significantly fewer cattle in the year prior to the survey (20.1 heads), than the non-adopters (83.4 heads), suggesting an inclination to pursue alternative pathways to livelihood other than the prevailing, most destructive pathway – cattle ranching; and they were more engaged in local farmers labor sharing associations (61.3% of RAPP households) than their non-RAPP counterparts (46.1%), indicating a greater engagement in civil society activity.

In practical policy terms these findings suggest that development project designers need to pay attention to the original attitudes of farmers regarding forests, tree-planting, social participation, and alternative ideas of livelihood behavior. The rural population is not homogeneous, and lots of good investment resources may be wasted operating on this assumption. The rural population is heterogeneous. Project designers, please find those specific farmers in the population who have a predisposition to manage forests, plant trees, and the domestic capacity to do both. Henry David Thoreau said the rest: “I have great faith in a seed. Convince me you have a seed there, and I am prepared to expect wonders.”

4. Timber-based agroforestry promotes reforestation? Fewer than one-half of the RAPP farmers designed agroforest plots primarily consisting of long-growing timber species; most opted for short-term polycultural systems or mixed (timber and ground crop) systems. However, our research indicates that those who did adopt the timber-based systems were more likely to allow secondary forest succession to occur around their prized timber plantings (e.g. mahogany, Brazilian cedar, cherry and teak). [Click here for slide show].

After 18 years, many of the timber-based agroforest plots in RAPP resemble the natural forest cover of the Amazon before the farmers first arrived. Now, however, these small agroforest plots contain valuable hardwood timbers that could provide the RAPP farmers’ descendants with a sizeable financial endowment. In 2005, the reported stumpage price for a mature mahogany tree (4-8cubic meters) was up to US$ 20,000, more than most of Rondônia’s farmers earn in their productive lifetime. In 1985, when most of Rondônia’s farmers sold stumpage rights to loggers they received US$ 5-10 for the same tree. [Click here to see Powerpoint presentation I gave at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association of American Geographers in New York City, revealing several LandSat chrono-sequences of secondary forest succession on RAPP experimental farms].

5. Spontaneous Diffusion and Independence – “We Can Do This on our Own!” We originally anticipated that agroforestry practices would organically spread among the rural communities in which RAPP experimental farmers were embedded, without external interventions, given that an estimated 50% of the rural population reported a desire to plant trees as part of their farming systems in our 1992 baseline survey. In the experimental corridors of the RAPP (those road sections embedded with RAPP farmers), 18% of the neighboring non-RAPP farmers spontaneously adopted agroforestry, in one form or another, (i.e. more through the influence of their RAPP neighbors than through RAPP project interventions). On the control corridors, where there were no neighboring RAPP farmers, agroforestry practices increased by only 5.4%. In other words, the desire to adopt tree-planting was so great that the “neighborhood demonstration effect” of the RAPP was sufficient to catalyze a significant number of newcomers to find ways to adopt this agroforestry practices into their farming systems without any external project support.

This interesting finding leads us to consider the obvious possibility that farmers, left alone, will adopt new practices, will innovate, when they see it in their interests, and they will do so spontaneously through informal communication and lateral exchange without external instigation or extension agency interventions. Many in this population want to plant trees and rebuild their forests.

The farmers participating in the RAPP project also revealed some profound attitudinal changes regarding their relationships with forests over time. Here is a sample of unsolicited comments from our RAPP farmers:

- “The size of the trees on my land, and the abundance of wild animals amazed me… Here in Rondônia, the forest provides many resources. We don’t need to cut forest. Instead, one can use the forest resources in order to survive.”

- “The planting of trees should have been started long ago. If I had planted trees since the beginning, I would have some money from that right now.”

- “The forest is a source of hope, because of its many resources. We depended on wood and rubber in the first years. Now, we talk a lot about whether or not to cut new forest areas. We don’t like cutting forest.”

- “If I had alternatives, I wouldn’t clear forest anymore. My intension is to keep as much forest as possible.”

- “I feel better in the deepness of the forest. There, I can listen to the animals. When we clear the land, the area becomes hotter.”

- “Only God knows why I did not die. Malaria came really strong on me! No health assistance was available, and most farmers had no money to buy drugs. Everybody suffered a lot. We had to carry people on our backs… Yes, we wasted a lot of wood resources from the forest…, we moved with our bodies and our courage… [Now] we have been able to survive. Before Rondonia I did not even have a place to live, now I do.”

Lessons Learned from RAPP:

- A small financial grant (in this case $250,000) can make a difference in exposing fallacies of conventional wisdom and can improve the lives of rural people, opening new insights into sustainable development.

- More times than not, the local participants, “beneficiaries” in development projects will retrain the development “experts” with their indigenous knowledge, ingenuity, and resilience. Most successful development projects come from lateral transfer – farmers teaching farmers.

- Social learning leading to household food security is the key outcome of successful development, not increased income (which is often short-lived).

- Commit to the long-term – Donors, let’s not kid ourselves – a long-term 5-10 year commitment, at least, is necessary to really deliver and understand project outcomes for long-term sustainability. Our donor wanted results in 3 years (we extended to 4). If we had initially been granted 10 years, we might have transformed our project study sites into large-scale community-based sustainable development landscapes – reforesting large areas of deforested tropical wastelands into economically productive agroforestry landscapes capable of retaining a rural population, now largely gone. Keeping the rural people on their farms is the only effective tropical forest conservation strategy for the Brazilian Amazon.

I was very fortunate to have Marcos Pedlowski as a doctoral student in the 1990s. He supervised most of the ground operations of the Rondônia Agroforestry Pilot Project while doing his doctoral dissertation on the role of the World Bank and non-governmental organizations in the Rondônia regional development plan at the time. Now, Marcos is a full professor at the Universidade Estadual de Norte Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro researching agrarian change issues (check-out Marcos at pedlowski.blogspot.com) (see photo of Marcos and Dra. Bertha Becker, below). Thank you, Bertha and Marcos, for your amazing contributions to our contemporary foundational knowledge of Brazil. I am so proud to be affiliated with you both.

Chapter 5 (2002-09) Whither the Brazilian Peasantry in Brazil’s “Post-Frontier?”

After 20 years of work in the Brazilian Amazon, I found myself returning to spend every summer in Rondônia, especially watching closely the rural community of Rolim de Moura, where my research career in the Amazon began in 1984. After 30 dizzying years of rambunctious expansion, it would be difficult now (2007) to characterize contemporary Rondônia as an overheated frontier. Population growth rates, which averaged 16% per year in the sizzling 1970s, dropped to a comparatively cool 2.1% in 2000.Today, the market economy is firmly established in Rondônia. World market prices for beef, coffee, and cocoa can be accessed daily at internet cafes scattered throughout the larger towns in the States. Satellite dishes dot the landscape. This once distant outpost at the end of a national telegraph line is now integrated into the national highway network and global telecommunication systems, and is poised to become an international trade gateway once the new Pacific Highway is fully opened. Most of the State’s rural population is now connected to a state-wide electrical power grid. Malaria, once a regional epidemic, has been largely tamed in the older settlements. Porto Velho, the state capital, a backwater depot of the rubber boom 100 years ago, is now an emerging regional metropolitan center hosting coffee houses, book stores, art galleries, tattoo parlors, a federal university, daily commercial jet service to the rest of the country and, alas, sprawling peri-urban slums. However Rondônia might be characterized, one would be hard-pressed to still call it a “frontier.”

So, what will become of the small family farm in Brazil, a foundation of Brazilian society? Will the frontier family farm survive in Brazil’s post-frontier?

Will large scale corporate agribusiness ultimately consolidate the myriad of family farms that dotted the frontier landscape, transforming, once again, Brazilian agriculture into a corporate export-oriented, cash-crop enterprise? Who will feed Brazil?

Before reaching into these important questions, I would like for you to know something about the life-stories of the pioneers who settled the Amazon frontier between 1975-1985). I am aware that these people are different from the last succession of peoples who settled the land now called Rondônia, the indigenous peoples, who life stories may never be told. Geographer Carl Sauer, referred to the landscape as life-way artifacts of different cultural successions. As part of the background research for the RAPP, we conversed with several of the pioneer women in the RAPP group, whose stories of migration to the frontier, bring important dimensions of this reality into view. [click here to visit their Portrait Gallery. This story and the photographs are published here with their permission]. We tend to think of frontiers in masculine terms. In fact, human livelihood in the frontier is fundamentally a female-oriented phenomenon. None of these [male] pioneers would have survived for long without the women in their lives!

Carlos and Marli Pinheiro (psuedonymns) were born in Parana in the south of Brazil. Carlos’s parents had migrated from Bahia to work as sharecroppers on a coffee plantation in the South. In 1977, Carlos, then 21 years old married his childhood sweetheart, Marli, then 17. By then, the coffee plantation where his father had worked for a decade was sold to an agribusiness in São Paulo; the talk of soy beans made prospects bleak for sharecroppers. When they heard that the government was giving away free land in Rondônia, Carlos and Marli decided to move there. Each of them packed a small suitcase; they had no other possessions but the clothes on their back and they took the Cascavel busline to Ouro Preto D’Oeste, a 3 day trip on the BR 364 (then a dirt road). [Click here to read on].

In 2002 with a grant from the National Science Foundation my colleague, geographer Robert Walker and I conducted a comparative survey research project of two distinct settlement frontiers in the Brazilian Amazon, one along the Transamazon Highway in Pará state (Walker) and the other in Rondônia (Browder). The sample frames of the survey were designed to include rural households that Walker had previously surveyed in 1996 and those that I had originally surveyed in 1992 as part of the RAPP. This research design enabled us to analyze some incipient longitudinal changes in the agrarian population over time, and to compare those experiences at two different settlement frontiers.

In 2002 with a grant from the National Science Foundation my colleague, geographer Robert Walker and I conducted a comparative survey research project of two distinct settlement frontiers in the Brazilian Amazon, one along the Transamazon Highway in Pará state (Walker) and the other in Rondônia (Browder). The sample frames of the survey were designed to include rural households that Walker had previously surveyed in 1996 and those that I had originally surveyed in 1992 as part of the RAPP. This research design enabled us to analyze some incipient longitudinal changes in the agrarian population over time, and to compare those experiences at two different settlement frontiers.

The results of these surveys were divergent, suggesting two independent frontier realities were occurring. But, there were similar trends as well. For example, in both Pará and Rondônia study sites, average farm sizes diminished over the respective study periods as pioneer farmers, now aging empty-nesters, began subdividing or selling-off pieces of their original farm allotments. Correspondingly, the rural populations of both study sites decreased. Not surprisingly in both sites the proportion of productive land area in annual (subsistence food) crop production declined. Use of formal credits (agricultural production loans) increased in both sites. These are among the benchmark characteristics of conventional frontier transition theory – the progressive subdivision of the family farms leading ultimately to consolidation into large-scale modernized commercial agricultural production systems, the associated shift from subsistence to cash crops, increasing capital penetration, and rural depopulation.

Still, important differences between Pará and Rondônia suggest a more nuanced frontier story. Among those differences, we found that Rondonian farmers had deforested a significantly higher percentage of their primary rural land holding (71%) than their counterparts in Pará (50%). Yet, Rondônia’s farmers had more years of formal education (3.3 years) compared to the farmers in Pará (1.3 years). A higher percentage of rural property owners in Pará (33%) also owned urban properties than in Rondônia (21%), suggesting greater access to markets, information and services not generally available to those who live in the countryside alone. The opposite trend occurred in multiple rural property ownership, where in Rondônia 35% of the sample owned more than one rural property than in Pará. Perhaps, most curiously, while the proportion of total land holdings in pasture production remained the same in Pará (at about 26%), Rondonian farmers more than doubled the size of their pastures (from 20% to 45% of their land holdings) over this 10-year period (1992-2002). These findings challenge claims that the frontier transition experience is homogeneous across settlement theaters, that expanding capitalism unifies outcomes. Important differences between our study sites suggest that those experiences are the results of distinct social, political, and economic processes underway in what is loosely called the Brazilian Amazon frontier. But, there is one important generalized exception to this claim that diversity prevails – In both frontiers, cattle herd sizes increased consistently, and in the case of Rondônia, exponentially.

Will the Brazilian family farm, the traditional mainstay of Brazil’s agricultural economy, persist in the growing face of globalization or will it dissipate into isolated remnants of rural poverty? We addressed this question in our 2008 paper, “Revisiting Theories of Frontier Expansion the Brazilian Amazon…” published in the journal World Development. [Click here for article Part I and Part II].

The World Bank and PLANAFLORO

During these 30 years in the Amazon I had the opportunity to work three times as a consultant for the World Bank. On one of those assignments I was tasked with evaluating a specific program that the Bank financed as part of the Rondônia Natural Resources Management Project (PLANAFLORO), the “Community Initiative Program,” an ambitious attempt by the Bank to ramp-up an integrated conservation and development approach to the regional scale. Two years after completing the assignment the Bank permitted me to publish some of the findings of my 6-day mission. The resulting paper, “Conservation and development projects in the Brazilian Amazon: Lessons from the Community Initiative Program in Rondônia,” published in the journal Environmental Management (2002). [], became my most popular reprint request. The World Bank was to be commended for attempting this admittedly experimental investment, the results of which moved us up the learning curve on integrating conservation and development.

Reading Colonist Landscapes

What do smallholder farmers in the Amazon think about when they decide to convert 2 or 3 hectares of forest to something else? This question captivated researchers, myself included, for twenty-some years, and produced a robust literature from a household level perspective. It was a time (mid-1970s to early 1980s) when many researchers assumed that farmer land use behavior could be explained largely by endogenous household characteristics (e.g. farmer education level, household demographics, household savings, etc.). What we could not yet conceptualize was how did exogenous factors influence smallholder land use decision-making. In an attempt to address this question, I integrated some salient data from the RAPP project data banks and subsequent research on the smallholders I had been following for 15-20 years. The result was a chapter, “Reading colonist landscapes,” in an edited volume Deforestation and Land Use in the Amazon. [Click here for article Part I ] The main conclusion of this research was that farmers’ experience the frontier differently depending on a variety of circumstances that congregate at the intersection of endogenous and exogenous life-spaces. I traced the different trajectories of 3 representative farmers, each following a very different pathway, and how different factors at both levels influenced their decisions. Colonists do not arrive in the frontier as a homogeneous population; they are different from each other from the start. And the processes of socio-economic differentiation continue long after they have established homesteads and become farmers on the landscape. The story of the frontier is summed-up in the aggregation of these individualized dynamics of internal and external forces operating on households, which are composed very differently from the onset. The end result is much more a mosaic of landscapes, each representing the situational rationality of individual people and their kin. It is an empirically pluralistic reality, that requires a pluralistic epistemology to understand.

Chapter 6 – The Globalization of Brazilian Agriculture in the Amazon Post-Frontier – Corporate Consolidation of the Cattle Industry (2006-present)

When my research in the Brazilian Amazon began in 1983, most of the region was in throes of tumultuous frontier expansion. Migrants were pouring into the frontier looking for land and work. Lumber mills proliferated on the fringes of the forests. They were followed by merchants, trading companies and, then by large corporations pushing cattle, then soy, then sugar cane, usually reaping lucrative institutional rents from government subsidies for nominal private investments. All of these frontier activities accelerated the rate of deforestation in the Amazon, most of which was associated with corporate cattle-ranching. Even so, the Amazon was a relatively small supplier of beef products and its herds constituted only 8.2% of Brazil’s national cattle herd in 1970 . Foreign direct investment in the region was minimal, except for bauxite mining and wood pulp production. The region remained an extractive frontier on the periphery of the emerging global economy. By 2002 this scenario had vastly changed. Foreign companies were subcontracting Brazilian suppliers of soy beans, sugar cane for ethanol, and beef products. The Amazon’s cattle herd leaped to 57 million animals, constituting nearly one-third of Brazil’s total bovine livestock population, which had grown to become the largest in the world. Exports of Brazilian beef soared from 269,000 metric tons in 1995 to over 1 million in 2003, bringing Brazil’s US$ 1.3 billion in foreign exchange. This gargantuan expansion could only have occurred with a major structural transformation of the Brazilian cattle industry into a global oligopoly. This transformation provided yet, another, topic of research.

With another research grant from the National Science Foundation (2006-2011), geographer Robert Walker (Michigan State University, www.geo.msu.edu/faculty/walker.html) and I undertook a study of this transformation and its implications for economic activity and environmental change in the Amazon. Our central questions were what function(s) does cattle production in the Amazon region serve in Brazil’s expanding domination of the global beef market and how has that expansion influenced patterns of land-cover change in the Amazon post-frontier. [Click here for slide show]

We proposed a conceptual model to explain the development of the Amazon cattle industry, and in particular to reveal the impact of globalization on Amazonian forests. The model specifies a transitional framework with three general phases defining the sector’s progressive integration with more distant markets – from regional (Amazonian) to national (Center-west/Southeast) to global markets, in a process that starts with early regional development efforts in the 1970s and continuing well into the first decade of the 21st Century (Figure 1,click here). It is important to note that the conceptual framework as spelled out conceals important spatial variations in the structure and function of the sector within Amazonia. Nevertheless, a generalized pattern across the region is evident.

In the first phase of disarticulated diversification, during the early years of the contemporary Amazonian frontier in Brazil (roughly 1968-80), economic activity on the terra firme occurred in isolated pockets along emergent transport corridors. Such activities were functionally and spatially disarticulated from national and global markets, with a few notable exceptions (e.g. the mahogany timber boom of 1980-85). This resulted in a regionally fragmented space economy characterized by diversified economic activity. Beef and dairy production in the Brazilian Amazon were driven, for the most part, by local consumer demand, especially in the region’s growing urban areas. The dramatic migrations to the Amazon in the 1970s and 1980s, and the rapid urbanization that followed, created high density population centers that fueled regional demand for cattle products such as beef and milk, especially in the larger urban centers such as Manaus, Belém, and Porto Velho. With a virtual monopoly over local markets, regional cattle producers had little incentive to adopt more efficient (i.e. land intensive) production techniques (e.g. feed lots, rotational pasture management, etc.). Since (forest) land was abundant, growth in production was accompanied by a corresponding expansion in forest conversion to pasture, often preceded by a preliminary stage of annual cropping.

In the second phase of articulated integration (roughly 1980-97), transportation (especially highway) investments created possibilities for national market integration, enabling the articulation of the cattle sector across nationally linked production chains. In this period regional cattle producers, while still supplying Amazonian markets, found increasing opportunities for expanding sales of more specialized cattle products (e.g. breeding cows) to the South. At the same time, technological modifications in animals and forage grasses allowed for greater productivity, and new margins for profit. During this phase, the national cattle industry followed a cyclical production pattern with periodic price swings. As prices increased, major producers retained steers from slaughter, only to “cash in” at the high point of the cycle, triggering a sharp plummet in prices, a “stampede” to the slaughterhouse, and liquidation of herds (including breeding cows) beyond their capacity to restock themselves. Evidently, in the articulated integration phase, cattle production in the Amazon supported the national cattle industry, in part, by producing replacement stock (calves and breeding cows) following such major liquidation episodes. Specialization in calf-breeding among a significant segment of the small landholder population in the Amazon suggests that they played a crucial role in the national cattle production chain.

National market integration induced technological improvements in Amazonian cattle production (e.g. improved breeding, animal health, new forage species, and improved pasture management). At the same time, the growing national market for Amazonian cattle products increased pressure on forests and encouraged the widespread land use shift away annual cropping to cattle ranching, even among small holders, and the decline in perennial tree-cropping (e.g. coffee, cocoa, black pepper, and other agroforestry crops) that many had hoped would provide a sustainable approach to Amazonian land use.

In the third stage (roughly 1997-present), the globalization of the Brazilian cattle industry followed in the wake of neo-liberal policy reforms aimed at expanding exports of Brazilian agricultural products, which have climbed steadily, especially in the beef sector. With regulatory initiatives to eliminate sanitary barriers to Brazilian beef abroad, Brazil now certifies certain production zones and large slaughterhouses as “hoof-and-mouth disease-free,” enabling a rapid expansion of its beef exports abroad. As noted earlier, exports of Brazilian beef skyrocketed in the late 1990s , to a US$ 1.3 billion trade. While nearly 70% of Brazil’s beef exports have gone to the European Union, beef exporters are expanded into other markets, including the U.S., the Pacific Rim, and the Middle East (Peck, 2003). In addition, there is some Pan-Amazon livestock trade, decidedly slanted toward Brazilian imports mainly from Venezuela and Bolivia.

Global forces now appear to play an influential role in the behavior of Brazil’s national cattle industry. But the nature of these forces and how they influence the Amazonian cattle sector and land use remain open empirical questions. .

In particular, there are at least four possible supporting roles that the Amazon’s expanded cattle sector plays in the expanding globalization of Brazilian agriculture during this period. First, the region’s cattle sector may be supplying domestic Brazilian consumption, thereby enabling large-scale producers in the Center-West and South-East to specialize in the more lucrative export markets. Second, frontier producers may participate in the export business as contract suppliers to large Brazilian beef processing firms configured into multi-nucleated production networks throughout the country. Third, transnational companies could be establishing Brazilian beef processing franchises as direct foreign investment in the region and purchasing steers directly from Amazon ranchers, as Parmalat (an Italian company) has done in the dairy sub-sector (purchasing milk). And fourth, Pan-Amazon livestock trade could serve local demand for beef in the Brazilian Amazon, thereby enabling regional producers to focus on the national market.

While more definitive conclusions await further data analysis three observations are clear: First, since 2000, Brazil’s cattle industry successfully penetrated global beef product markets supplying a demand especially in Europe left unmet by local production due to mad cow epidemics. Second, the rapid globalization of Brazilian beef cattle production was accompanied by significant structural changes in the Brazilian cattle industry, mainly the agglomeration of production chain control by a small number of well-financed Brazilian investors creating an oligopoly of 4 or 5 companies by 2005. Third, the subsequent consolidations of the beef cattle production chain entailed ripple effects into the populist family agriculture as small-scale Amazonian farmers shifted from mixed-crop production systems to pasture-based cattle production mainly to supply local and regional markets. This probably resulted in higher commodity prices and a greater push to convert remaining patches of forest found on family farms.

I have no doubt that cattle ranching for global beef markets, especially robust in the Pacific Rim, will become a permanent and dominant land use in the Brazilian amazon, especially so when the new Estrada ao Pacífico (the road between the Brazilian Amazon and the Pacific ocean) becomes fully operational. But, soy and timber (also in high demand in the Pacific Rim), not to mention ethanol from sugar cane, are likely to continue to expand as the primary motors of the region’s economy. The region’s original geo-socio-political importance as a “labor safety valve” for the peasantry will dissipate over time, and Brazil, now with the Amazon “fully developed,” will still face an internal reality of brutal inequality and continuing poverty – except for those small family farmers that figure out how to become resilient through diversification of their production strategies when it leads to food security and fuller participation in the market economy.

Conclusions

Amazon Development – Five Contentious Assertions (1995)

On February 24, 1995 while on sabbatical at the University of Florida, Gainesville, writing Rainforest Cities, I was invited to lead a graduate seminar there and offered these 5 Contentious Assertions about Amazonian Development to provoke some focused discussion:

1. Capitalism as a mode of production is not significantly established in the Amazon region, although expeditionary capital has from time to time penetrated the region. Explanations of patterns of regional change predicated on the assumption of capitalist expansion (based on the North American frontier model) need to be revisited pertaining to the Amazon.

2. The role of the State in regional change in Amazonia has never been homogeneously coherent. Rather, it has been ambiguous, vacillating, and differentiated among competing bureaucracies and interest groups at the national level and between national, state, and local governmental agencies.

3. Community-based conservation strategies cannot be effective without strong public governance institutions able to consistently guarantee common property rights and other civil liberties. Non-governmental civil society organizations alone cannot substitute for stable democratic governance.

4. Rural-urban dichotomies are problematic in Amazonia. The degree of interaction between rural and urban social groups and economic interests and population movements have obscured any clear functional distinction between so-called rural and urban sectors. That said, the Amazon is predominantly an urban frontier.

5. Yet, urban growth in Amazonia is functionally disarticulated from both agricultural development and industrialization in the region, but is spatially differentiated in its functional linkages to economic forces operating at the global level.

Two years later, when Rainforest Cities (1997) was published by Columbia University Press, we added two additional general observations:

6. Amazonia, although displaying all of the trappings of the American wild west of the 19th century, was born urbanized. So, too was the American frontier. Yet, Amazonia is a heterogeneous social space, defying categorization as a “peasant frontier” or a “bigman’s frontier.” Such conventional labels are too rigid and antiquated to accurately represent the complex patterns of spatial organization in contemporary Amazonia. Rather, the “Amazon frontier” is as much mystique as reality, a social construct imagined from the optics of outdated conceptual frameworks, like “capitalist penetration theory”, “inter-sectorial articulation theory,” “central place theory”, dependency theory, and normative neo-classical economic theory. These theoretical frameworks still have much to say as we gaze on the patterns of development in the Amazonian frontier. But, now, we must recognize that much of the occupied Amazon is no longer a “frontier”, and it’s time for old theories of frontier expansion to give way to new paradigms of social change, political behavior, and environmental justice in the Amazon Post-Frontier, yet to be written by the next generation of Amazonistas. Bring em on!

7. The configuration of settlement systems in Amazonia is irregular and polymorphous, disarticulated from any single master principle of spatial organization or regional development. Diverse settlement systems abound and there is considerable asymmetry in the patterns of regional settlement, reflecting the distinctive logics of settlement location both between different contemporaneous spaces and overlaying historical epochs upon the same spaces. Different geographies are everywhere. The divergent nature of past Amazon regional development patterns suggests that the region’s intersection with the global economy in the current “post-frontier” is mediated by local forces in different ways in different sub-regional spaces. In other words, no one single pattern of development will uniformly spill over the region as a whole. The story of the Amazon cannot be written as a single conceptual narrative.

Then, in 2012, ten final observations, entailing recommendations for future research, seem warranted:

8. While the emerging regional network of frontier urban settlements in Amazonia is still a work in progress, especially on the more recent active fronts, the region’s major metropolitan centers (Belem, Manaus, Cuiaba, Santarem) have become important theaters of globalization who recent rapid growth has gone under-investigated. Future research on Amazon urbanization would be fruitfully focused on the growth patterns, dynamics and consequences of the region’s swelling major metropolitan areas.

9. Many areas of the Amazon are now well into a second generation of occupation, meaning they have entered the “post-frontier”. However, the post-frontier in Brazilian Amazonia is not a certain or predictable reality, but displays many of the multiplicities of newness found in the irregular patterns of development in the frontier phase of regional expansion. That said, the Amazon, despite its democratization, its enormous natural resources and biogenetic wealth, remains a largely subordinated periphery, dominated by increasingly globalized corporate interests centered in Sao Paulo, Brazil’s historical economic centrifuge. Two additional topics of future research would be promising to pursue: (1) foreign direct investments with local enterprises in the region that bypass Brazil’s traditional corporatist elites in Sao Paulo, and (2) the changing influence of Amazonian civil society (NGOs, social movements), as the region becomes integrated into different circuits of global capital. How both streams of change influence the region’s political and economic autonomy will have important implications for global climate change and biodiversity management in the 21st Century.

10. Brazil’s persistent problem of inequality has not been ameliorated by the occupation of the Amazon region, indeed the Amazon experience, so far, has exacerbated poverty and inequality in many geographic arenas, especially those characterized by extractive economic activities. The most important arena of emerging regional poverty in Amazonia is not in rural areas, but in the rapidly growing shantytowns appearing on the peripheries of the Amazon’s metropolitan centers.

11. Capitalism has been redefined by the Brazilian Amazon experiment in Amazon regional development. It is no longer about wage relations of production, but short-term production contracts, systems of production driven by flexible capital accumulation strategies, increasingly involving global corporate interests.

12. Such accumulation strategies not only reinforce existing socio-economic class disparities in Brazilian society, but further entrench a small politico-economic corporate elite as master controllers of the Brazilian economy, whose private interests are served by perpetuating the dominant system that reinforces these disparities.

13. Yet, the counter force of an emergent, vibrant non-governmental/non-profit sector of civil society frequently gives hope and inspiration that someday Brazil will find, for the first time, an independent cultural and political identity not bounded by its colonial legacy or by the forces of contemporary corporatist global capitalism. I am hopeful.

14. This dominant system can be regulated by credible governance institutions and practices; Brazil’s post-1985 democratic renaissance has demonstrated this possibility on several fronts. And, democracy cannot rely on a civil society infrastructure alone – governance institutions are the bedrock of civil society.

15. But, democracy in Brazil will never resemble republican democratic practice in the United States or the pluralistic parliamentary politics found in much of Europe. Culture, intermixed with history, exigency, and spontaneity intervene to stymie our passion for ontological standardization. Brazil is a unique cultural formation that will always defy our western conceptual templates and translations.

16. The legacy of colonialism lives-on in Brazil, seemingly embedded in the culture’s psyche. But, I stop short of asserting that Brazil’s is locked-into a dependency relationship with the world system. Indeed Brazil has become a regional super-power, spawning its own multi-national corporations that will be reckoned with on the global economic stage. Ironic, that such economic independence at the national level is accompanied by a persistent pattern of “endo-colonialism” regarding the Amazon. How will this beautiful, gentle rainforest world, the largest vestige of tropical wilderness, and it native peoples, survive the ravages of globalization? I hope for a new model of development that manages to preserve the authenticity and integrity of this robust ecosystem and its human inhabitants, both native and new.

Early on in my dissertation research I kept hearing Brazilians use an idiomatic expression, “voltado para fora” to lament everything they found to be wrong with Brazilian society. It translates into “oriented to the outside”. In other words, it conveys the sentiment that Brazil’s dependency on the outside world accounts for its problems today and implies a certain legacy of colonialism. Curiously, the expression has no singular meaning in the vernacular Portuguese of Portugal. Eventually, while researching cattle ranching in the Amazon, one rancher respondent quipped, “nos somos mal-definido como um povo porque o brasileiro sempre chegou aqui com motivo de voltar para fora” (“we are poorly defined as a people because the Brazilian always arrived here [Amazon] with the goal of returning to the outside). I never forgot this Brazilian rancher’s off-handed comment because it spoke to a larger characteristic of Brazilian cultural identity as a “colonized people” that has sublimated into Brazilian national consciousness, surfacing periodically in the form of this common linguistic expression heard only in Brazil. I don’t know if the same expression occurs in other countries colonized by Portugal or in Spanish America. It is an intriguing phenomenon how language, like landscape, contains our “unwitting autobiography”.

17. I personally grieve over the continued destruction of the Amazon’s primary rainforests – clearly sacred places that I have visited multiple times with awestruck humility, witnessed first-hand their destruction, and sought to rebuild them thereafter. I have tried to dedicate my career to understand why they are being destroyed, and then, how to rebuild them in the ways that seemed sensible. A seed of change emerges from the ashes of the rainforest in the Rondônia Agroforestry Pilot Project. Hopefully, it takes root.

18. This brings me to a final reflection of my 30-year journey in the Amazon: Since the patterns of development that I have observed in Amazonia since 1983 do not conform to the predictions of many leading theoretical paradigms that have competed for explanatory hegemony over the last 50+ years, we are left with the unsatisfying, but enticing possibility that localism prevails on the ground. Globalization, if seen as a bulwark of restructuration toward ever more homogeneous patterns of production, consumption and development, does not, in the end, win the day here. But, perhaps the forces of globalization also emerge from locality, asserting themselves opportunistically in ways that are not entirely controllable from distant boardrooms, thereby reinventing globalization itself. Stepping back, to take full view of this amazing phenomenon called Amazonia, and the 30 years I have been privileged to dwell within it, I walk onto the broad stage of conceptual pluralism. Here in this enormous organic epistemological riot, there is the realization that multiple rationalities of individual livelihood and powerful global forces of spatial organization co-exist and intermingle to continuously re-invent this restless landscape that is history’s last great terrestrial frontier – and, in many important ways, therefore, humanity’s final autobiographical statement.

The Will of the Amazon

By John O. Browder